Tai Chi: In-depth introduction to history, philosophy & benefits

Oct 07, 2024

Years ago, when I went to my very first Tai Chi trial class, I really didn’t know anything about it. I thought it was a slow martial art for the tired and elderly. Although I wasn’t old, I certainly did feel very tired, so I thought it might be right for me.

It was the beginning of a journey of discovery. Through Tai Chi, I learned about Daoism, the Chinese philosophy on whose principles Tai Chi is founded. Dao, or “Way”, turned out to be something I had instinctively felt connected to but never knew how to describe. Wikipedia says it can “be roughly thought of as the flow of the universe, or as some essence or pattern behind the natural world that keeps the universe balanced.”

Both patterns and the notion of flow have always appealed to me. When I first encountered the flow that can be experienced in practicing Tai Chi, I recognized the pattern, both physically and spiritually.

The thing about Dao is that it does not advertise. It is there if you want it, as in-your-face yet obviously overlooked as the air we breathe.

Dao does not go out of its way to say, “Hey, look at me; why don’t you join me? Sign up here!” What a funny notion. Dao has no marketing budget, and it knows no missionaries either.

Tai Chi, as an exponent and expression of Dao, therefore did not yell at me from a flashing billboard. It waved a modest hand at me from within.

It said very quietly, “Hello. I am here for you if you want me.” I needed something, so I paid attention. I saw the wave and heard the whisper. And unlike so many times before, I chose to listen to this invitation to connect. It changed my life.

At the end of this article, you will have more than a basic understanding of Tai Chi. We will go back to the origins of the art form to understand the principles and philosophy behind this healing practice. So if you’d like to learn about what Tai Chi is and what it can mean for you, please read on.

Chi, Qi, Ji: What Are All These Chees About?

A brief explanation of the philosophy that underlies Tai Chi is needed here. Tai Chi is a physical expression or practice of this philosophy, so it will help you to know what you are doing.

First, a brief point on language. Tai Chi comes from China, and as the phrase goes, “they speak a different language there”: Chinese. When we talk about these things in English, similarities and differences between these two languages can both help and hinder. Let me help you not be hindered by them.

We will first talk about Qi, say “chee” as in “cheerleader”—a fine image indeed, for cheerleaders abound in Qi.

Qi 氣

Qi is vital energy. It also means ‘breath’. In English, we have taken similar words from Latin spiritus and speak of'respiration','spirit', ‘inspire’, ‘and'spiritual’. When someone is alive and in a good mood, we say they are in high spirits; when they pass on, we say they have given up the ghost. The breath of life has passed from their lips; there is no more life energy in the body—no more Qi.

Just like temperature, Qi cannot be seen, but the effects of changes in Qi can be observed. You may wake up feeling full of the joys of spring, bounce through the day from this task to that, and then, come four o’clock, you think, What happened to all that energy I woke up with? Change of Qi. We can expend it, and we can accumulate it, too.

Tai Chi is one fine way of regulating and enhancing our life energy, our Qi.

How?

Harmonizing Opposites to Make Qi

Kenneth S. Cohen, the author of The Way of Qigong, writes that Qi “can be defined as the energy produced when complementary, polar opposites are harmonized” (Cohen’s italics). Think of how steam arises when water and fire are unified. Steam powers engines; Qi powers all that lives.

Tai Chi, in turn, practices and stimulates this process of harmonization. Both within ourselves and between ourselves and our environment. Harmony, Kenneth Cohen explains, leads to the ability to “make better life decisions, informed by the whole being rather than a particular, dissociated part.”

So what are these “polar opposites," then? Well, in the West, we often think of the heart and the mind as separate and often conflicting entities. Likewise, the body and the heart/mind do not always seem to be aligned. Arguably, it is beneficial to harmonize these so that your mind isn’t running in one direction and your body in another.

In ancient China, however, heart and mind were considered one and the same (心xīn: “heart-and-mind” or "heart-mind"), and the body was included in a holistic view of the living creature. The harmonization that produces Qi, therefore, is about something else.

The harmonization of polar opposites that Tai Chi, which Daoism is founded on, is to do with yin-yang.

From Chaos to Yin-Yang and Tai Chi: An Origin Story

To understand Tai Chi and yin-yang, we need to briefly visit the origin of life, the universe, and everything. Daoist philosophers believed that first there was chaos. Not as in “complete disorder and confusion," but simply in its original meaning of “primordial matter before there was form.”. From Graham Horwood’s Tai Chi Chuan and the Code of Life: “A state of undifferentiated opposites, which existed in a ‘pre-heaven state.”

Through the principle of Dao, chaos manifested itself and became "nothing with something around it”: 无极 wújí, anglified as Wuji. This literally means “there is no pole" or “does not have an utmost point.”. Infinity would be one way of understanding that, insofar as we can understand infinity. Over time, Wuji came to signify the “primordial universe.” The origin of everything. Infinite emptiness: we depict it as an empty circle.

Wuji

Then an unknowable process of separation took place; I tend to imagine a sort of centrifugal spin cycle. Perhaps this is what happens when you try to contain infinite energy. This process resulted in the more clearly recognizable opposite poles of yin-yang, represented in the symbol of the Tai Chi Tu in Chinese太极图tàijítú.

Do you see the second character there, jí 极? That is exactly the same as in Wuji无极 wújí. We pronounce this more like the “jee” in “jeep” than the “chee” in Qi-rleader. So the common English spelling of Tai Chi can be a bit confusing because we write "Chi," which sounds like Qi, which it really isn’t. The romanized spelling of Chinese, pinyin, is more precise about this: tàijí. For this reason, English-speaking Daoists often prefer to write Taiji rather than Tai Chi. Now you know why you may have seen both.

Tú 图 simply means “picture” or "diagram," so this is the diagram of Tai Chi, which means “supreme ultimate.” The highest, greatest, or farthest extremity or pole.

Tai Chi

Yes, this is the symbol you may well have seen before. On a T-shirt of someone in your yoga club, in the window of the local esoterica shop, or tattooed on somebody’s arm. Intuitively, we understand that it expresses a kind of balance. The two interlocking, fish-like figures, the black and the white, contained within the infinite flow of the circle (which, you now know, is Wuji) It does express harmony, doesn’t it?

Black and white. Positive and negative. Light and dark. Wet and dry. Inside and outside. Left and right. Heaven and earth. Heads and tails are the two inseparable sides of all kinds of coins. Yin and Yang, although we never say it like this. Rather, yin-yang, precisely because they are not separate but forever connected and complementary. We recognize one because of the other.

Two interlocking fish, then. As you have learned, all existence comes from a state of undifferentiated but contained chaos: oneness (Wuji). Daoism, therefore, encourages a return to that state of peaceful oneness that has no end and no beginning. Peace: harmony. By harmonizing the two, the polar opposites that cannot exist without each other, we can attain this peace. From Tai Chi back to Wuji. The washing machine begins to spin and by spinning, it separates one from the other…

Anyway, back to the story.

A History of Tai Chi: From Philosophy to Fitness

The ancient Chinese philosophers, much like their Western counterparts, embarked on a quest to understand the world by observing nature and its patterns. This pursuit led to the development of Daoism, a philosophy deeply rooted in naturalism and the observation of the universe, or "All-under-Heaven" as they termed it. This concept included celestial bodies like the stars, and it reflected the Daoist view of the Dao as the manifesting principle of the universe.

The regular cycles of the sun and moon, the change from day to night, and the cycles of life and death in the natural world all piqued the interest of these early Daoist thinkers. They observed the inherent balance in these cycles, embodying the yin-yang principle, a foundational aspect of Tai Chi philosophy and an observable practice reflecting the Dao.

The concept of yin-yang balance is evident in the practice of Tai Chi, a Chinese martial art that aligns with the principles of Daoism. Tai Chi movements are designed to mirror the harmonious balance found in nature, and the practice itself is a form of Daoyin, an ancient form of exercise aimed at guiding and stretching the body following these principles.

After observing the universe, some shrewd Daoists took to learning from it. Hua To, a Han Dynasty doctor and boxer (really!) had a keen eye for the principles of behavior in the animals that he studied. He noticed how the animals lived in harmony with their own nature as well as the nature of which they were an inseparable part. The bird flies. The tiger pounces. The monkey scratches and snatches. He developed a theory that animals stay healthy because of this harmony. And because they move in the way that is most natural for them, if we, as human animals, can move like them, he reasoned, we can become and stay healthy, too. Yes, like me, you may detect a bit of a logical leap there. But that’s how it happened: the creation of Daoyin,导引 dǎoyǐn.

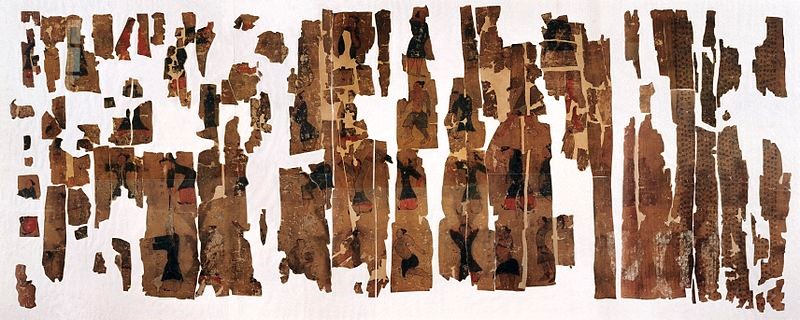

Daoyin chart for leading and guiding people in exercise (source: Wikimedia Commons)

Daoyin was probably one of the first comprehensive health-and-fitness regimes in human history. Stretching, breathing, self-massage, and more to improve circulation, flexibility, and balance. Well before Jane Fonda did her videos. But a kind of calisthenics nonetheless. Hua To called his fitness program ‘Five Animal Play’, which some contemporaries who thought it all rather silly dubbed ‘Five Animal Frolics’, to make fun of the early Daoist practitioners whom they saw imitating tigers, bears, monkeys, and birds in the forest.

Wudang Five Animal Qi Gong with Master Gu

Little did they know that this Qi Gong or Qi work—work that benefits Qi—proved to be so effective that it rapidly gained massive popularity, which it enjoys to this day. Your reading of this article is proof of that.

Daoyin, Qi Gong: Tai Chi

What started out, then, as an expression of a philosophical origin story was thus developed into a form of preventative medicine: a wholesome routine for young and old alike. People who lived in harsh environments or circumstances—in the fields and in the mountains, for example—experienced these health benefits firsthand. Because it requires so little space and no other instrument or tool than one’s own body, it can be done at any time and any place.

Certain monks in the Shaolin temples in remote parts of the Chinese mountain ranges took to practicing Qi Gong, too. Over time, they recognized that the ways in which animals move can also be useful in dangerous situations for self-defense. And so they adapted the Qi Gong into many different styles of martial arts, which we now call kung fu (功夫 gōngfu). Tiger Style, Crane Boxing, Praying Mantis, Snake Hand... From there, everything took flight, which has given rise to what we now know as judo, karate, aikido, kickboxing, tae kwon do, and many others.

Animal Kung Fu Styles

In these centuries in which these so-called 外功wài gōng, or external martial arts (designed for physical combat), were developed, there were those, too, who inspired a return to the founding intentions of Qi Gong: self-health rather than self-defense.

One such legendary figure was Zhang Sanfeng. We know little of when he lived, but estimates place him between 960 and 1279 CE. Some evidence points to Zhang Sanfeng having been a scholar of Confucianism as well as a gifted and diligent student of Buddhism and of the external martial arts. Zhang was a scholar who knew how to throw a punch.

He went on to study Daoism and then lived as a hermit, which brought him (and now us) to the Wudang Mountains in Hubei Province. It was there that he founded his own monastery and school for the practice of 内功nèi gōng, or internal martial arts: exercises that benefit the internal organs, Qi, heart-and-mind and more.

The author in front of the statue of Zhang Sanfeng in the Wudang Mountains

This is how Wudang has come to be the birthplace of Tai Chi Chuan, the martial art that we now simply call Tai Chi (or, as you have discovered, Taiji). Chuan means "boxing,” and Tai Chi Chuan is often referred to as "shadow boxing.”.

I’ll come to that in a bit.

The snake and the magpie

Rigour and strenuous practice were obviously no strangers to Zhang Sanfeng. Legend has it that one night he was instructed by a Daoist Immortal to reform his training methods. Instead of applying the “hard” style that he had learned at the Shaolin temples, he could devise a way to overcome the hard with the soft.

This is the sort of dream that tends to stick in one’s heart and mind.

It troubled Zhang Sanfeng until one day he witnessed a fight between a snake and a magpie. Some sources say a crane, but the old frescoes in Wudang temples depict a magpie, so let’s say it was a magpie. Even if a crane seems to correspond better to how we move in Tai Chi... It was a bird, at any rate.

A fresco in Purple Heaven Palace in the Wudang Mountains.

Note the bird and the snake in the bottom left-hand corner.

Zhang saw how the snake would raise its head and draw its body back, coiling into a powerful spiral spring before striking. Similarly, he observed how the bird used gravity to stab down at its enemy and how it would deflect attacks with diagonal swoops of one of its wings.

Like the Daoist naturalists before him, Zhang Sanfeng translated these movements into a system of physical exercise called Tai Chi Chuan. A true Qi gong form, Tai Chi Chuan aims to benefit one’s health and stimulate the internal harmonization of Qi. Certainly, it is Chuan (boxing); when performed fast, the external, “martial” aspect is clearly visible. Practiced slowly, Tai Chi takes on a meditative character where the gōng, the work, is done on the inside, facilitated by precise, balanced breathing and absolute but natural control of the body—from within.

One to Two, Two to Three, Three to Many Styles

Over the centuries, many students came to Wudang to learn this enchanting new martial art style. They were shown how the soft overcomes the hard, just as it is advised in the seminal works of Daoism, the I Jing and Laozi’s Dao De Jing. Students discovered that the natural progression of up and down, forward and back, left and right occurs simply by letting gravity work for them and by flowing like water through these yin-yang changes.

One such practitioner was Chen Wang Tin, who lived in the Chen village of Chen Chia Kou in the Wen district in the sixteenth century. Chen further developed and adapted the techniques that had come out of Zhang Sanfeng’s inception of Tai Chi Chuan in the Wudang Mountains centuries before. To this day, Chen Style is often acknowledged as the modern foundation of Tai Chi.

From Chen came Yang Style, a young member of the Yang family who, first in secret, then as an accepted pupil, spent many years studying Chen Tai Chi with the Chen family. He would go on to take it to the imperial court, and over time, Yang Style spread all over the globe and is practiced by large numbers of individuals and groups today. For a long time, it enjoyed recognition as the “official” style of Tai Chi Chuan.

Nonetheless, there is also Wu Style, Sun Style, Lu Style, and various other branches and offshoots. As Master Gu likes to say, Tai Chi Chuan is like a tree with many branches, and Wudang is its stem.

Shadow-boxing for Health

Tai Chi, a renowned Chinese martial art, continues to captivate practitioners worldwide, not only as a cultural expression but also for its extensive health benefits, akin to added years of youthfulness. This ancient practice, deeply rooted in Tai Chi philosophy, enhances stability, balance, flexibility, and strength. Moreover, Tai Chi fosters a sense of inner peace and contentment, vital for holistic well-being.

In traditional Chinese medicine, which has evolved since the time of the Zhou and Han dynasties, health is not merely about curing ailments; it is more fervently about prevention. This perspective is echoed in the practice of Tai Chi. Similar to the everyday habit of brushing teeth for oral hygiene, Tai Chi serves as holistic hygiene for its practitioners. It is a proactive approach to maintaining and enhancing physical and mental health.

Tai Chi's approach to health is comprehensive, attending to both the body and the heart and mind regularly. This holistic practice is reflected in the style of Taijiquan (Tai Chi Chuan), a form that embodies the philosophy of yin and yang and the concept of the "five elements" from ancient Chinese traditions. The Tai Chi form, a sequence of movements, is designed to cultivate fitness, flexibility, stability, and a sense of freedom.

The term shadow-boxing, often used to describe Tai Chi, reflects its nature as an internal Chinese martial art. This term is linked to the idea of practicing fighting techniques without an opponent, similar to the training methods developed by the historical physician and pugilist Hua To, the father of Daoyin. In Tai Chi, these shadow-boxing techniques involve slow, deliberate movements combined into sets, each designed to align and harmonize the body's movements with the mind's focus.

Connecting Body, Heart-and-Mind and Intention

In Tai Chi Chuan—Chinese shadow-boxing—the martial aspect is expressed because there is a distinctly recognizable intent to each movement. As if there is an actual opponent facing us. The importance of visualization, therefore, cannot be emphasized enough. Without “seeing” that “shadow opponent” in front of us, we are just performing a lovely-looking dance. “Tai Chi dancing," as some might snicker.

This may look pretty, and beauty is important in Tai Chi, too, but what about those health benefits, then?

For these, we need to connect the body and the heart and mind. By opening ourselves to full awareness of ourselves and of our surroundings, by both realizing and strengthening the connections inside and out, we can become one (Wuji) while we move to the rhythm of the yin-yang change (Taiji).

Focusing on the imagined opponent

We visualize the opponent, follow them with our eyes, and anticipate their moves. Our focused attention, our intention, leads our Qi. We use our breath to send the energy where it needs to go. Similarly, to guide the opponent’s Qi past us, we do not need to overcome their strength at all. We sense, we anticipate, and we respond—with our heart-and-mind, our intention, our Qi, and our body all working in unison—because they are one.

In other words, Tai Chi has the power to reconnect us to what we are: One.

And in that experience lies infinity, or, as some would put it, immortality.

But perhaps you prefer a list.

Health Benefits of Tai Chi

Tai Chi provides:

- internal massage of the vital organs

- improved circulation and metabolism

- steady, full breathing that becomes the standard

- lower heart rate and blood pressure

- boosted immune system

- enhanced flexibility of muscles, tendons, and ligaments

- enhanced flexibility and “openness” of joints

- improved stance and posture

- suppleness and grace of movement

- reduced stress levels

- increased resilience

- mental clarity and emotional balance

- awesome ability to stand on one leg for ages, e.g. to tie one’s shoelaces

These are some of the observable effects on the health and wellbeing of somebody who regularly practices Tai Chi. Centuries of the continued popularity of Tai Chi throughout Asia and more recently in the Occident, too, provide evidence for these benefits. Western science has also begun to map and measure what Tai Chi can do for an individual’s health. If you would like to read more about this, I recommend, for example the two books mentioned previously: Tai Chi Chuan and the Code of Life by Graham Horwood and The Way of Qigong by Kenneth S. Cohen.

In Conclusion

We have journeyed from the origin of the universe to martial arts and beyond. From the supreme ultimate to animal frolics. We have discovered that Tai Chi is an expression of the guiding principle of everything that exists; and that Tai Chi is a type of Qi gong, a system of movement for health and wellbeing.

You might also be interested in an introduction to Tai Chi as told by Master Gu himself. Watch this video to learn more:

Now you have an understanding of what “Tai Chi” means. And what it can mean for you. Let me conclude by sharing what it means to me.

Whenever I practice, Tai Chi helps me reconnect. I feel more grounded. Better equipped to deal with the hustle and bustle of modern life. I am calmer in the face of the storm. I enjoy life more. It is the one thing that helped me from day one of a year of burn-out. Tai Chi led me to Daoism, Wudang and the Wudang Taoist Wellness Academy, and Master Gu. To my friend, brother, and fellow traveler George Thompson, to becoming a disciple of Master Gu as a brother in the Sanfeng Pai, the school of Zhang Sanfeng.

Tai Chi has taken me to experiences I could never have dreamed of as a Western, early-middle-aged English teacher who used to be running in the rat race of life in the Netherlands.

Tai Chi, or Taiji Quan, transcends being just a martial art; it is a philosophy and a way of life. Practitioners worldwide, guided by the teachings of early Tai Chi masters and supported by resources like North Atlantic Books and Wayfarer Publications, continue to explore the depths of this practice. Tai Chi helps not only in addressing specific health conditions but also in maintaining overall well-being, embodying the essence of Chinese tradition and the seamless integration of martial arts and traditional philosophies.

I do not exaggerate when I say that Tai Chi has opened up the world for me. Outside: new places, new people; rivers, mountains, monkeys. Inside: new insight, light, balance, inspiration, inner peace. A blog, a podcast, a book. A Daoist name. A new perspective.

I can’t promise that it will change your life to this extent. But I can say with every confidence that if you connect with it, it will signal a new beginning.

And a peaceful, powerful and beautiful practice that will bring you

福 寿 康 宁

fú shòu kāng níng

Happiness Longevity Health Peace

Have fun practicing!

First steps of a new form: enjoy the experience

---

Eli Roovers, Taoist name: 丹宁资和

16th-generation Sanfeng Pai disciple and Taoist Wellness Instructor